Not only that, in his spare time, he sits on a technical subcommittee for CMAA (the Crane Manufacturers Association of America), an independent trade association affiliated with the Material Handling Industry (MHI) as assistant VP of Engineering, where, alongside CMAA president Dan Beilfuss, VP Molly Wood and Warren McDaniel, VP, Engineering, to make the industry a proactive and safer place to work.

OCH: Sylvain, what drives you as an industry leader?

SR: Designing custom cranes, where no two projects are the same. Our purpose is to deliver maximum value for our customers starting from the bidding processes to the design, fabrication, and finish with site acceptance tests. That’s what drives me. We manufacture custom-made equipment on large gantry cranes, which is a huge challenge for us. For example, a large US hydro client.

We worked with this US hydro client to manage the dams on some rivers in Washington and Oregon State. The gantry we delivered was for an emergency gantry that could lower at the same time, three gates simultaneously, to close the penstock for a turbine. So that was three times a 195-ton gantry. The project lasted about three years, but it's very rewarding once everything is up and running flawlessly on site.

We're a multidisciplinary company, so we do all our engineering in-house. We have mechanical, electrical and automation engineers. So, at the start of every project we know who the lead designers are and how to go through all quality processes and design reviews together. The challenge is to take into account all previous design experiences and learn from any mistakes to ensure the job runs smoothly and on time.

OCH: What is your biggest business inspiration?

SR: Being able to respond to technical challenges and demanding applications. We manufacture custom cranes, so we do not have a standard design, but we build according to the needs of our customers. But that technical challenge to respond to a very demanding need is what drives me.

I am not afraid of taking on a challenge for example, we had to design a crane for a University in British Columbia which was going to handle a hot cell (radioactive material) and that radioactive material was generated from a particle accelerator to make medical isotopes.

The purpose of the crane was to handle that hot cell and not only handle it, but to be single failure proof. That means to be able to hold and secure the load in the event of a single failure, but also have high availability in order to secure the hot cell into its lab container so people could access the area and maintain or repair the crane.

It was very challenging, because we had to make sure the crane was highly secure but also had a lot of availability in order for people to be able to secure the load and access the area.

Another example is a project we did for a US aluminum producer, in Spokane, Washington State.

They had seven transfer cars loaded with aluminum and they needed to send them from one location to another. But the transfer cars had to move in a way that involved different sequences to load the plates and send them to another area. So, there was a backup transfer car with six transfer cars right next to a unit they call a stretcher.

They were loading from the stretcher and then to get the furthest car out, you had to shuffle all the other cars out, then bring the two remaining cars and the backup transfer car back in line to be able to continue loading. That was more of an automation challenge than a mechanical one.

OCH: What is your business philosophy?

SR: To provide the best solution for the most technically challenging job. After that, to be able to provide the best cost for value for the technology we are implementing into our equipment.

It's always a challenge to manage the amount of engineering hours we're consuming to solve a technical solution.

OCH: Why and how did you enter this business?

SR: When I graduated university, it was during the recession, so it was difficult finding a job. When I went to my interview at COH (Canadian Overhead Handling at the time) all the people interviewed were smartly dressed in a suit, but because it was summertime, I decided to wear a pink shirt, leather tie and summer pants. I think it was my enthusiasm and personality that won them over and that’s why they hired me.

What I found out afterwards is that it helps to have a big personality and enthusiasm to work in a small company. You have to be able to stand your ground, make your point and be able to defend it. I guess that’s why I was successful because I'm still here.

It’s interesting because at that time I had to learn about the components being used to build a crane.

At university, I knew the principles, but I never applied the technology. My mentor at COH was an experienced Norwegian electrical engineer who had a lot of practical knowledge, but no theoretical knowledge. So, I had to learn a lot of new ways of

OCH: Tell us about your success stories?

SR: I have many success stories but the one I’m most proud of is designing the transfer systems for the truck plants at car manufacturer all over Canada, the USA and Mexico.

At the time, this client had one of our frame turnovers, a crane and a robot used in the production of trucks. When they are built on a frame, the frame is turned upside down so the workers can start putting the parts that go into it, under the truck.

Once the parts are installed, they have to flip it back over. The machine has front and rear rotation, so it picks up the frame, raises it, rotates it as it transfers, and then sets it onto another conveyor.

We’ve supplied equipment including a body marriage where they take the body of the truck and marry it to the frame and frame loaders, where they load the frames onto the production line. All this equipment is fully automated within the robot cell, where they run one cycle a minute, 24 hours a day, almost 365 days a year.

We started producing them in 1990 and some of them are still operating today. It's a very sturdy piece of equipment, and I'm quite proud of what we were able to accomplish.

OCH: Tell us about your failures and how you overcame any challenges?

SR: We don’t have any failures where the equipment could not be brought to production, but there are always challenges.

For example, we had to provide a Spillway Gate Hoist, for a hydro client in South Carolina, which is a hoist that raises a gate so that the level of a reservoir can be brought back to a comfortable level, so it doesn't flood. The challenges we faced there, were with the gearbox on 11 hoists.

We had to limit the forces exerted by those hoists so that the structure wouldn't crumble.

And limit the maximum force that the hoist could exert on the gate so that it wouldn't collapse. What we found out, was that the limits we had set at the beginning were too low due to the gearbox inefficiency which would absorb part of the motor torque, preventing us from seeing the real weight of the force.

It took a while to find out where the problem was but once we detected it, we could compensate by using a higher motor torque and still limit the maximum amount of force that the hoist itself could produce.

OCH: What do you like about this business?

SR: I love the fact that we make custom cranes, it's never boring because it always changes even if some of what we do is similar, such as hydro energy.

I mentioned the powerhouse cranes and gantry cranes we provide and the truck handling and dam project and what I find fascinating, from an electrical side is that technology evolves much faster than the mechanical portion of the crane.

A piece of steel is a piece of steel. Once you know how to weld it and arrange it, it's mainly repetitive. But, on the electrical and automation side, we try to make sure we provide the newest available technology to minimize the obsolescence of the equipment we're delivering to our customer.

All the automation components are talking to each other so that we detect any possible faults that could arise.

The danger of overhead equipment is that once you're lifting your load, you're accumulating potential energy and if you're not able to control that, it could be disastrous.

We're used to dealing with those challenges and making sure that we manage our design to prevent a catastrophe from happening.

OCH: What do you dislike about this business?

SR: Time spent away from family. For example, when we did the truck plants project that was a very busy period for us and involved lots of travel.

Those periods are very challenging because in the US there's a couple of holidays that are used for shutdowns. So, Christmas, New Year's Eve, Easter time, 4th of July, Labor Day and Thanksgiving. Those were the periods when we were very solicited and where we were not able to be at home with our family.

At the same time, it was also very rewarding because that's where I got all my experience. Learning on the job so that when you encounter problems onsite you understand the reality of the situation. I always tell my designers, you have three priorities in this order: site, shop and project.

OCH: What makes your company unique?

SR: Our technical capabilities; being able to design equipment that meets very difficult technical challenges. And being able to exchange technical information with our customers. For example, when we did a big project with the US hydro client, the engineers were fairly green in crane design, so we had to educate them on some detailed and sophisticated specifications.

Sometimes they write things without really knowing what's behind it, so that was a difficult and long process that we were finally able to achieve with them, being able to help them understand the reason behind the selection of certain components and how we design the structure for strength and stability. Being able to share our technical expertise with the customer is much more rewarding than having a spec where they say you can do whatever you want.

OCH: What is your view on the future of the overhead cranes business?

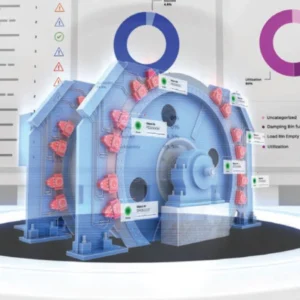

SR: What we are trying to achieve now within the group is to set predictive maintenance components.

Mainly a computer that would read the parameters coming from the electronic components on the crane and be able to say there's a degradation on that component.

That's going to be the challenge on future pieces of equipment, to be able to detect if there's any possible degradation and address these so customers can preventively maintain their equipment instead of repairing it once it breaks.